|

||

| . . . Chronicles . . . Topics . . . Repress . . . RSS . . . Loglist . . . | ||

|

|

| . . . 1999-07-09 |

Everywhere I've browsed in the last week, I've seen links to a horrible misogynous disgusting pornographic poem.

Well, these are a few of my favorite things(1), and so I finally gave it a look. Oh man(2). What pretentious tripe(3).

Now back in my day(4), they knew horrible misogynous disgusting pornographic poetry. As witness this lyric by John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, which I often recite on public occasions(5).

After reading that, a palate-cleanser is called for. Unfortunately, most of Wilmot's best poems are too long for me to transcribe(6). But here's something suited to my age and position.

| . . . 1999-07-22 |

After a week of gout, Cholly's in the worst of moods -- which makes it the best of times for punditry.

The "pre-"-prefixed villains above all shared the misconception that a Web designer can ease the reader's experience by cutting up a single lump of content into arbitrarily-sized and carefully-packed-away pieces. But the human eye and brain are designed to work together to find elements of interest in larger contexts: losing the current context during our scan simply slows us down. (Predictably, "accessibility" is one of the shiny buzzwords joining the fray, even though the only possible defense for bite-sized-Easter-egg hierarchies is that they might speed up browsing for the vision-impaired, who can't so easily scan through a long page.)

Hypertext evangelists attack linearity, but a work of literature is not a one-dimensional line: it's a two-dimensional object striving for the illusion of four dimensions. One of those dimensions is time, which we assume to be unidirectional, but, if anything, the classic literary text overturns that assumption by emphasizing the nonlinerarity of experience.

Hypertext might be able to provide more thematically appropriate surface structures than traditionally printed text. (Or it might not. The hypertext I'm proudest of has gotten more enthusiastic responses from readers who've read the flattened-out printed version than from those who've encountered it only as hypertext.) Even so, the virtues of a particular hypertext can never be called virtues of hypertext in general, and making a piece hypertext doesn't confer on it any special positive quality. It's like saying that the wah-wah pedal created a musical revolution. Play it, Prunes!

| . . . 1999-08-07 |

It's got its good paragraphs, but E. E. Cummings's allegorical reading of Krazy Kat -- with Kat as democracy caught between Mouse-anarchy and Pupp-fascism -- has always rubbed me the wrong way.

For starters, Cummings refers to Krazy as "she" throughout, whereas the strip used "he" much more often. (Bowing to public pressure, Herriman experimented with unequivocal she-ness once, but decided it just didn't suit that dear kat.) Following a natural train of thought, Ignatz's rage could be better described as homophobic than as anarchistic: he hates Krazy not because Krazy is a symbol of authority, or repression, or respectability, or even stability, but because Krazy is eccentric, flamboyant, unaggressive, affectionate, and a little kwee.

For the main course, any historically-dependent reading misses Herriman's achievement: a complete universe grown from one necessarily inexplicable but endlessly fecund triangle. Jonathan Lethem came closer to the mark in his story, "Five Fucks," where the triangle is a mysteriously universal solvent; even Lethem took the easier way out, though, in making the triangle violently entropic rather than pleasurably generative.

As Herriman demonstrated in later strips ("A mouse without a brick? How futile."), Coconino's reality depends on support from each point of the triangle; as he demonstrated throughout the strip's three decades, the triangle supports an infinite unfolding of reality. Lacking that central mystery, other comics, no matter how minimalist or how beautifully drawn, seem artificial and puffy by comparison.

| . . . 1999-09-20 |

Cholly's just back from Los Angeles, and the big news in the LA Weekly seemed to be cosmetic surgery, which takes up as much space as the Web and sex combined in San Francisco papers: thirty large ads before the movie listings. Breast implant before-and-after shots, skin abrasion, nose breaking, bone scraping, hair reshaping, wrinkle stuffing, lip puffing, liposuction, hard questions ("Incision - Underarm vs. Nipple Vs. Bellybutton?"), and one thing so awful I don't even know what it is and I don't think I want to, either:

Complimentary Power Pill with consultation!

This is the most disturbing mystery I've wanted to keep mysterious since reading the conclusion of Chinese Gastronomy's entry on "live monkey brain of Kwangtung":

"Any sauce?" we asked. He just shrugged. "The usual soy sauce and ginger." He went on to the description of another small horror called "Three Peeps" -- a descriptive name which requires no further elucidation. It was served with the same sauce.

| . . . 1999-10-15 |

I guess it's been worth living here for over eight goddamn years just so's I could reap full enjoyment from this week's San Francisco Bay Guardian....

| . . . 1999-10-26 |

Modern Art: Steven Elliott's and Christina La Sala's "Invisible Practices" installation has made SF State's Art Gallery over into a spacious windowless studio apartment for today's narcissistic Invisible Man, fully furnished with a "now you don't" business suit, a T-shirt for Casual Fridays, a bed, reading materials, inspirational wall hangings, and even a sandbox.

After the opening celebration, we settled down with La Sala at a noisy restaurant, ordered a lot of beer, and opened our note pad for an exclusive interview with the artist. A transcript follows:

Sierra Nevada?It sure is. It sure is....

No. Yes.

California part.

I went to Copperopolis.

No copper. Ghost town.

Not where invisible man came from.

C gets to proofread.

As long as I don't stand out.

Invis not part of body.

Nothing to do with body politics.

Clarify!

Not butter.

Times when it's good.

High-school.

Visible - bad things happen.

Elvisopoly.

[trade secrets]

Detergent - completely artificial.

Sneezing gasping wheezing.

Not nature.

Scotch tape, xerox.

6 + 4 is 12

More insulting to call it scottish tape.

Hop scottish.

Drinking game.

(looks like) notor Lielb

That's a good interview.

| . . . 1999-11-18 |

I like reading Hannah Weiner because spirits dictated her poetry to her, and her spirits seem a lot more believable to me than occult blarneyers like Mrs. Yeats's or the brunchtime natterers of James Merrill. Her spirits are petty, obsessional, cranky, dull, and mean -- just like dead people should be.

It's hard to find many people who've read any Weiner, and this, by Mara Damon, is the longest essay I've found about her. Unfortunately, it spends most of its time arguing with its own navel, which seems a waste of the perfectly argumentative navel built into Weiner's work....

| . . . 1999-11-20 |

Modernist Class

I remember reading to him a German translation from a speech by Radek in which the Russian attacked Ulysses at the Congress of Kharkov as being the work of a bourgeois writer who lacked social consciousness. "They may say what they want," said Joyce, "but the fact is that all the characters in my books belong to the lower middle classes, and even the working class; and they are all quite poor." I know he was a convinced antifascist.

-- Eugene Jolas

Underbred.... the book of a self taught working man....It's sleight of hand, a kind of shell game. A few flourishes of the shells labeled "Modernism" and "Postmodernism" keep us from noticing the writers who have not been shoved into them and from noticing the essential differences between the writers who have.

-- Virginia Woolf on Ulysses

Class, for example.

Yeats's, Pound's, and Eliot's works were in defense of a dreamlike aristocratic status; they loathed the city, or, more specifically, the city's middle class and the city's poor.

Pound and Eliot first became interested in Joyce as a semi-articulate witness to those urban horrors, a sort of Dublin Dreiser. And they lost interest in him as the serialized episodes of Ulysses left realism behind: he was no longer a witness but a class-climbing eccentric who somehow assumed that the world owed him a living. (Biographers still seem to have trouble with that notion, but one should bear in mind that the world of the time seemed perfectly content to supply Yeats, Pound, Stein, Woolf, and so on with livings.)

By the time we get to Louis Zukofsky and Lorine Niedecker (if we ever do; they're still not part of standard academic curricula), those beastly New York Jews and bestial Midwestern immigrants who so offended Henry James are actually writing, without apology, as if they could possibly fit into some respectable (and quite imaginary, thank the lord!) society....

| . . . 1999-12-08 |

Recently received:

I was reading a Bean Bag Monthly magazine and saw a listing for a Bubba Gump Shrimp bean bag.I have searched the web site and did not see it listed, how can I purchase one?This isn't quite what I was getting at by that quote about "my pleasure in your response," but I guess it still counts....

| . . . 1999-12-10 |

Modernist Class

You can tell by the jarring sound of "Zukofsky" in The Trouble With Genius : Reading Pound, Joyce, Stein, and Zukofsky that Bob Perelman is better read than most academics. He's also better to read: his observations are sensible and accurate.

But those being observed are "Modernist," and Perelman is "Postmodernist." And, apparently as a result, his tone is one of such versatile hostility that no book could escape censure. He holds the proselytizing rhetoric of critics against the writers' own works, and he's pissy about these four writers in particular 'cause they weren't able to meet the supposed "Modernist" ambition of perfect synthesis of every conceivable human goal. He provides a brilliant short introduction to the unique virtues of Ulysses and then claims that the lovely object he just described is proof of Joyce's ineptitude.

But it's not all that clear that such weirdly individualistic writers as Joyce, Stein, and Zukofsky actually ascribed to the dopey ambitions Perelman posits, except inasmuch as any working writer has to deal with them: Sure, we got to try to do the best we can think of doing, right? And that can get pretty inflated before it gets punched down. And what we end up with is never quite what we thought we were doing, but sometimes it's still OK, and we can at least try to have a sense of humor about the yeasty smell.

After that performance, Perelman's sequel book, a collection of upbeat reviews mostly of his fellow Language Poets, is about as convincing as the happy ending the studio slapped onto Face/Off. Despite their own lunatic ambitions, Perelman's compeers don't piss him off the same way Joyce, Stein, and Zukofsky did. Why? 'Cause they're "Postmodern" and so they're smart enough to undercut their own claims to textual mastery.

The trouble with that is that The Trouble with Genius spends most of its time showing how those stuck-up Modernists also undercut their own claims to textual mastery. I mean, out-of-control-ness is pretty much what you (and Perelman) notice in the second half of Ulysses or in almost anything by Stein or Zukofsky, and it's pretty fucking arrogant to claim that such a pleasurable (and obviously labored-over) effect is attributable to blind error with those guys any more than it is with Ron Silliman or Susan Howe -- or with Melville, Dickinson, Austen in Mansfield Park, the indomitable bad taste of Flaubert, or the wild line-to-line mood swings in Shakespeare, for crying out loud.

At the end of the book, Perelman says that blanket-statement theorists, snippy critics, and it-is-what-it-is poets are playing an unproductive game of paper-scissors-rock. Probably that's a fair assessment, at least when any of them are responding to professional challenges by the other players. But who except a rhetorically worked-up poet would say that a poem was a rock (let alone say that Ezra Pound was the Alps)? Who but an allegiance-drawing theorist would announce in print that any theorist was in any conclusive fermez-la-porte! sense correct?

What Perelman leaves out of his game and out of his book is the possibility of the reader. And publishing gets to be a pretty sad affair without an occasional appearance by that self-satisfied little cluck.

| . . . 2000-01-07 |

The San Francisco Bay area: William H. Chambliss had the style and humanity of a 19th-century Limbaugh ("Then a man named Booth took pity on society and killed Mr. Lincoln, to keep him from making a giant April fool of Uncle Sam..."), but he also had the gossip of a Drudge:

Married men who were determined to bring their wives out here were advised to steer well clear of San Francisco. They were told that any place in the State, even Sacramento and Oakland not excepted, would be better for married gentlemen who entertained hopes of raising children of their own.. . . These were not by any means the only interesting persons whom I saw at San Rafael. Besides Mr. Wilberforce, who always makes people weary when he attempts to talk, and Webster Jones, who is always talking about the quantities of wine consumed at the latest parvenu dinner party, -- but never mentions his father-in-law's "business," or past record, -- and Charley Hoag, who was looking around to see if there was anybody in the crowd whose name he did not have in the Blue Book ; and "Billy" Barnes, who ruined his prospects of getting the nomination of the "Octopus" party for governor, by publishing his picture in the Wave ; and Ward McAllister, Jr., whom C. P. Huntington appointed to a fat position, as Pacific Mail attorney, in order to curry favor with a certain leader of some of New York's prominent dancing people, there were some remnants of a crowd of silly parvenus who disgusted everybody of any refinement at the Sea Beach Hotel, Santa Cruz, in June, 1893, by putting "private parlor" signs on the reading room door.

| . . . 2000-02-03 |

"Thus an agreement may require constant reassurance and work at maintaining relationships to prevent breakdown. This, however, depends on the imperfectness of the conflict resolution obtained. It requires characters not to be quite sure of the common, conflict-free model to which they've converged. If they were sure of it, and it exhibited complete resolution, they'd have no need to bother about each others' feelings." (via Alamut)At the end of June, 1989, my lover of over eight years left me without warning and without explanation. She came home a little late and was gone two hours later. Two friends told me independently that they'd always secretly thought our relationship was too content to be healthy.

She married a lawyer from her office. I collapsed like a tower of pickup sticks.

And I wasn't the only thing to fall apart.

Who was that pre-Socratic who called the universal binding material "love," as opposed to "the weak attraction force" or "Elmer's"? That guy, yeah. Well, cold turkey withdrawal of the local binding material reduced everything to its constituent elements, and those aren't an appealing sight. Favorite books became ugly over-packed stacks of graphemes. Food was kuk. I couldn't crawl into a bottle 'cause the major constituent elements of even nice wine turns out to smell like poison. The idea that anyone would make noises on purpose seemed absurd. And I reverted to a pre-Griffith state as far as movies went: I could sometimes manage the illusion of movement, but connecting individual shots into a narrative was beyond me. I remember sitting through Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and having no idea why people around me were laughing. (Oddly, I still have that reaction to Seinfeld....) I was a bug pinned to a perfectly blank index card.

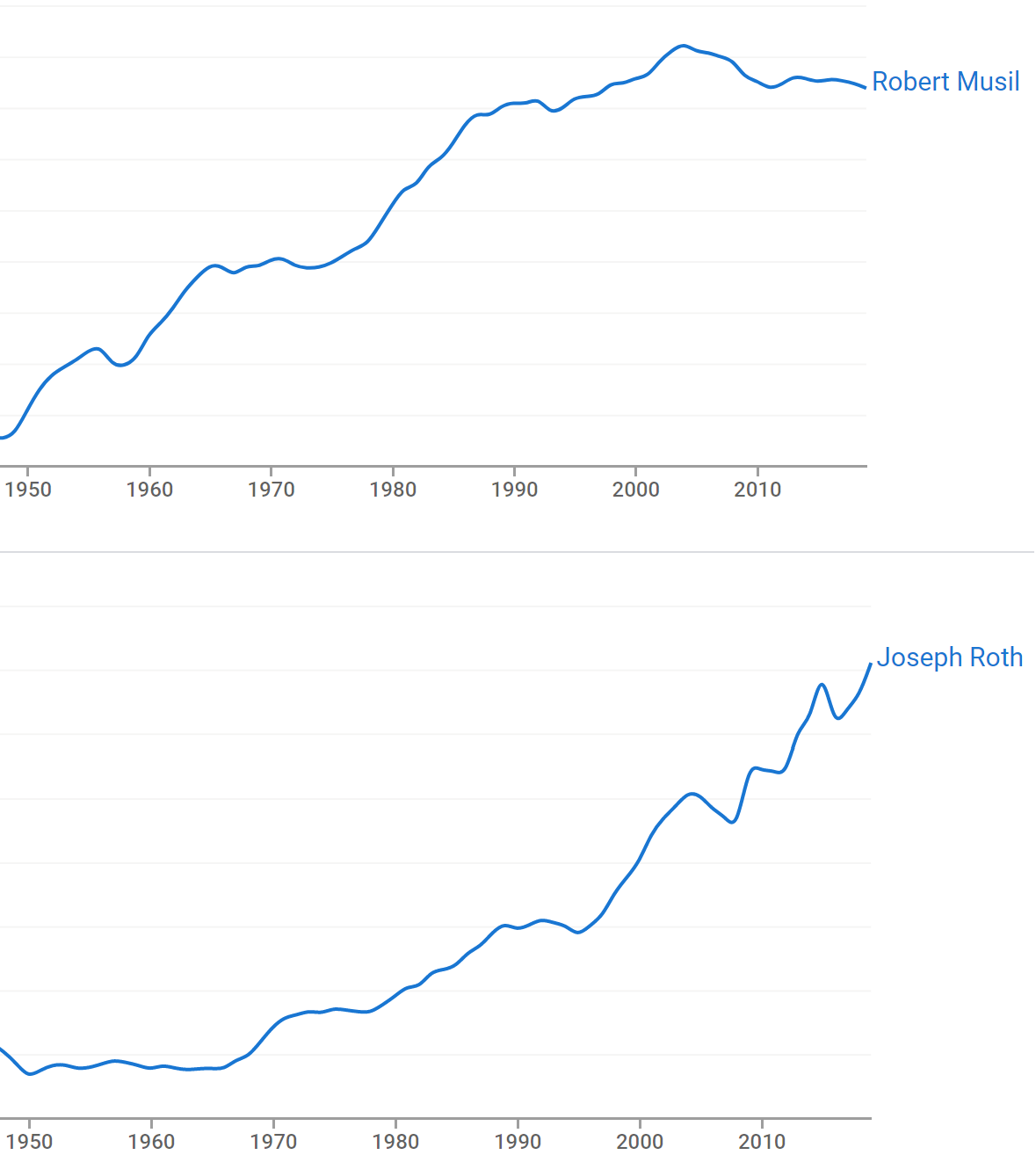

Like with other recurrent infections, the best way to get a pleasure back is to weaken your immune system with a new strain: Robert Musil's cold-blooded analyses of emotional extremities revived reading; I also encountered some Language Poetry for the first time and said, "Hey, this makes sense!" I was nursed, weaned, and set back to film school with a little pat on my fanny by repeated viewings of Cat People.

And so forth. Not so much getting over it as planting around it.

After a few years, even the nightmares dropped off. The last one I remember was from 1993 or so: I dreamt I got a phone call from my ex. She was crying, and I had to work to find out what she was trying to say. Finally she told me that she was really really sorry, but she had to sue me.

"Sue me?! What for?!"

"Somewhere between five and fifteen thousand dollars; it depends on your assets."

| . . . 2000-03-11 |

Nothing ages like senility: A tale of two libraries

The Little Leather Library is a set of teensy-weensy cheaply-bound booklets stored in a plain cardboard container about half the width of a sneakers box, marketed around 1920. My father had a set (presumably inherited from his father), and they made up a large part of my childhood reading.

The "leather" looks like the seal on rotgut bourbon, the paper is the color of burnt caramel, and the smell is pure nostalgia. Aside from that, the Little Leather Library's enduring appeal for me lies in its editorial hand, which rested heavily on "modern classics" (i.e., the fin-de-siècle). Here are some volume titles:

|

|

... and as a strapping middle-aged man, I was delighted to find the continuing education course that is The Golden Gale Electronic Library: a world-wide distributed database of texts viewable only with the the Golden Gale Book Reader program.

The program is -- well, let the coder without sins throw rocks at it; Greek font or no Greek font, I wish I could extract the whole text into an editor and be done with it -- but what a public service in these texts! Starting from the sizable splash of the leaden Benson brothers' upper-class Anglo-Catholic end-of-the-nineteenth-century public-school boy-mania, Golden Gale has captured over a hundred volumes of otherwise vanished ripples. So far, I've galed along to:

|

|

| . . . 2000-03-18 |

In Old Manhattan

Ray, reading aloud from the plaque on a fence: "Also buried here are such 19th century notables as: Preserved Fish, the merchant."

Laura: "You should write a biography."

| . . . 2000-04-21 |

Our motto

Certainly not a journal; not in the sense of diary, and not in the sense of magazine -- not so much editing the Web as muttering at it under our breath.

So NQPAOFU is right; correspondence is closer -- but letters tend to call-and-respond into ever thinner echoes unless frequently larded by topics from outside the letters themselves. For me, a still closer analogy is conversation, with its fragmenting veerings of immediate impulse, its easy changes of tone and subject, its relaxed or fraught (but inevitable) drops into silence, its emphasis on voice.... Most of what I've written began in speech, including my longest short stories and the projected novels I'll never finish (because I run out of talk before the novels run out of pages?). The weblog form presents fewer exceptions to that rule than ever, supporting variations on the reedy tenor from bitchy to maudlin to bumptious to ponderous to bubbleheaded to just plain reading out loud....

But of course a conversation made public and permanent is not quite a conversation any more, except in the sense of The Infinite Conversation: a conversation which leaves politely open the possibility that the person conversed with hasn't heard you or doesn't care to or doesn't even exist yet. (Here's where another meaning of correspondence comes in handy: a coincidence of distant experiences....)

By far the most addictive writing medium I've ever used was a piece of CRT-based software called DECnotes (or was it VAXnotes? I'm pretty sure it wasn't WINnotes, anyway). It was fast and centralized and accessible world-wide; it made it easy to create and track digressions and new discussions; a standard customizable text editor was built in. It painlessly combined aspects of essay, email, discussion, role playing, mob violence, annotated revision-tracking scholarship, and improv troupes: a Collected Letters and Comedy Hour.

I keep hoping that I'll find something similar again, even if only by having someone hire me to program something similar. In the meantime, I've cycled through not quite as addictive approximations of various sorts. The Hotsy Totsy Club is a closer stab than the others, but still lacks some visceral sense of contact that I miss, a sense of immediate rewards and immediate dangers, the pleasantly ambiguous challenge-and-collaboration of dancing or flirting....

| . . . 2000-06-18 |

| What proofs did Bloom adduce to prove that his tendency was towards applied, rather than towards pure, science? | |

| Insofar as wise critics have looked at science fiction, critical wisdom has it that the genre's most distinctive form is the series, and particularly the "fix-up": the novel built up of mostly-previously-published more-or-less integrated more-or-less independent short stories and novellas.

"I do not like that other world"

"More-or-less" being the distinguishing factor here. The close relationship of the pulp magazine and pulp novel industries led to many hero-glued fix-ups in other genres of popular fiction (Dashiell Hammett's and Raymond Chandler's early novels, for example); the short attention spans of protosurrealists, pseudosurrealists, and other artistes-fines led to a number of single-hero multiple-narrative (Maldoror, Miss Lonelyhearts) and single-narrative multiple-hero (As I Lay Dying) assortments. "After God, [insert name] has created most..."

But what defines sf is not a peculiar approach to character or narrative but a peculiar attention to the implied context of the fiction. This implied context is usually called the work's "world," as in the quintessential sf skill "world building" or the quintessential sf hackwork "shared world" writing. Because the constructed context is what defines a "work" of sf, a single sf "work" can cover a great deal of time-space ground (as in Robert Heinlein's "future history") and incorporate many different lead characters and closed narratives. "He's dead nuts on that. And the retrospective arrangement."

Given a long enough lifetime, sf authors sometimes start to wonder if all their worlds might somehow be "shared" in the all-in-one person of the author: Isaac Asimov's attempt to combine his Foundation universe with his Robotics universe to make Asimov Universe TM; Samuel R. Delany's multi-decade cross-genre remarks toward the modular calculus.... "...if the city suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book."

Outside the sf genre, what this reminds me most of are Jack Spicer's notion of the "serial poem," Louis Zukofsky's notion that a poet's lifetime of work is best considered as one long work, and James Joyce. (... further reflections generated by the essays in A Collideorscape of Joyce: Festschrift For Fritz Senn ...) |

As Jacques Aubert points out in "Of Heroes, Monsters and the Prudent Grammartist," child Joyce's writerly ambition, like that of many genre workers, was fired by reading heroic adventure stories: "Madam, I never eat muscatel grapes." And, also like many genre writers, Joyce continued (would "compulsively" be too strong a word?) to use the notion of the heroic (alongside the notion of author-as-trademark) as an organizing principle while undercutting it with a self-awareness that ranged from scathingly bitter to comically nostalgic.

In "Dubliners and the Accretion Principle" Zack Bowen very convincingly treats the collection of mostly-previously-published stories Dubliners "as a single unified work... the stories so interrelated as to form a type of single narrative" with a clear structural pattern and a loose but extensive web of inter-episode linkages. (A biographical tidbit unmentioned by Bowen backs this up: Joyce knew "After the Race" was a weak story but felt compelled to include it to save the overall shape of the book: a common architectural problem for the fix-up author.) On the next hand, Christine van Boheemen's "'The cracked lookingglass' of Joyce's Portrait" makes a case for breaking apart A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, since all the chapters use the same semi-self-contained bump-down-and-bounce-up narrative structure rather than gliding smooth-and-steady towards maturity: "Instead of psychological and emotional growth, the fiction depicts repetition." Each episode imagines itself to be first, last, only and alone whereas it is neither first nor last nor only nor alone in a series originating in and repeated to infinity.... Van Boheemen's approach would imply that the "final" flight to Paris on the wings of artistic vocation is merely another roundabout to the next repetition. And Stephen's bedraggled comedown in Ulysses, so embarrassing to those who pictured him ascending to glory at an angle of fortyfive degrees like a shot off a shovel, certainly seems to give her approach the edge. There hasn't been much need to remind readers of the heterogeneity of Ulysses, starting from its serialization episode by episode, each episode a chronologically, thematically, and stylistically closed unit. (Are there any other novels for which we refer to "episodes" by title rather than to "chapters" by number?) Timothy Martin reminds us again anyway in "Ulysses as a Whole" that inasmuch as anything can be said to tie the book together it's a shared context -- implicitly an externally documented day in the world, explicitly the inter-episode allusions and reflections, "many of them added late in the book's composition." As always, the limiting case is Finnegans Wake, whose compositional history also includes serial publication and last-minute blanket-tucking additions. But here the repetition and fragmentation go simultaneously down and up the scale to such an extent that almost no one ever reads the book except as scattered sentence-to-page-sized episodes semi-explained by references to other episodes: "holograms" and "fractals" became rhetorical commonplaces for Wake scholars as quickly as for sf writers. Maybe that's why Exiles seems like such a flimsy anomaly: it's a self-contained traditionally structured single work where a revue or a burlesque show might have felt more appropriate.... |

| . . . 2000-07-04 |

Special Anniversary Narcissism Week! (resumed): Audience

From the email interview with Mark Frauenfelder: How popular is your weblog?

Beats me. I've tried to not pay much attention since the hit counts passed those of my two ancient Yahoo!-linked pages.To Paul Perry:Unless you're advertising, popularity doesn't matter on the web. That's the whole point of the web as a medium: wide distribution is cheap, and therefore not dependent on things like popularity. I know the readers who'd enjoy my crypto-cornpone style are a small minority. I just want as many of that minority as possible to get a chance to enjoy it.

I used to tell my web design students that they should count success by the amount of nice email they got. I've gotten some nice email for the Hotsy Totsy Club.

Perhaps I'm overoptimistic, but I think the distinction between community and incest is easily maintained with a little conscious exogamy. As Aquinas says, incest is sinful because its cramming together of multiple social relations "would hinder a man from having many friends." To share an interest in a form is one thing, and a nice thing. To share all the applications of that form would be incestuous if consensual; simple plagiarism if not. Which doesn't appear to be a problem in the ontogroup you've posited -- I doubt that you and I have ever had a link or a line in common, for example -- probably due to the very things that interest us in the form....Answering David Auerbach: My question to you, about writing on the web: how do you react to the choice/imposition of a very imminent and particular real audience that trumps any thought of an ideal audience?

I recognize the words you're using, but I would've used them to describe my issues with print publication. The painfully particularized audience who happens to be subscribing to a particular magazine during my particular appearance or to have bought a particular anthology containing my particular story is (precisely because it's the target audience of the publications) more than likely to be bored or annoyed by my work.Web publishing, on the other hand, is only "ideal audience." There are no promises, no presuppositions in those fluffy network-diagram clouds; anyone might bump into anything. No "ideal audience" right away? Well, put the pages into the search engines and wait. No "ideal audience" ever? Well, at least it was cheap. On the web, the non-ideal audience will simply not bother reading what I've written; that is, it doesn't exist as an audience.

The biggest problem I have with web publishing has to do with that very fluffiness -- the lack of antagonism and risk means fewer itchy stimuli to respond to, less friction to push off against, less lying but more solipsism -- which is where I'm hoping that crosslinking, email, and public discussion can help....

Although it seems to make sense that conventional publishing should lead to more topical and less personal discourse, that hasn't been my experience. In the shorter forms of paper-publishing, anyway, public commentary tends to be driven by professional feuds and personal friendships, and private commentary restricts itself to messages like "Would you write something similar for my publication?"

Books are available to a more diverse readership and thus receive more diverse reactions, but book publishing is much more big-businessy than magazine publishing, and its barriers seem well-nigh insurmountable to the easily discouraged or stubbornly erratic.

I've gotten many more direct and diverse and therefore useful responses from web publication, partly because search engines don't worry about enforcing an editorial tone, thus allowing for more startle effect, and partly because email makes it easy to send responses.

As for the cult of personality, I'd be happy to admit that I think it's impossible to separate "voice" from "content" -- at least for the kind of content and the kind of voice I have. What journalism and academia might describe as the "privileging of content" or as "self-discipline," I hear as "mendacious (if useful) voice of authority," and it makes me sick with hypocrisy when I mimic it. Scholarly and commercial venues would be accessible if I could stick to the point, and hip venues if I could stick to aggressive role-playing; but when de-emphasizing the performative and the off-putting is required for writing, then I simply don't write. And since I still seem to want to write, I make the working assumption that it's not required.

| . . . 2000-07-09 |

|

||

|

||

|

| . . . 2000-07-12 |

Weblog hero David Chess is kind enough to suggest another example of loglike fictionlike pageslike:

If you don't mind sex, there's "Parents Strongly Cautioned" at "http://pastca.pitas.com/". He seems to be out for the rest of the month, but his previous months are well worth reading IMHO. No cheap porn (usually!) and very weblog-style (in some sense).PaStCa is indeed a cheering concoction -- how is it that porn is able to incorporate parody so easily without disintegrating into farce? maybe because love is funny ha-ha as well as strange? -- but its serialized morsels are a bit more self-contained than whatever vague yearnings trouble my virginal dreams....

| . . . 2000-12-03 |

|

Movie Comment: SHADOW LAND OR LIGHT FROM THE OTHER SIDE

Spectators huddle closely ("otherwise you won't see anything but a blur") around a rickety flickering contraption tended by a woman with an odd accent. We bob and weave so's not to miss a single tawdry apparition, strain our ears to catch the wavering, trite, obscure, and thrilling message. The images shimmer like silver, or silverfish. Effects were made the old-fashioned way: directly in the camera and shaken back out. The exaggerated planes of depth simulate, remarkably closely, late 19th century accounts and photographs of spiritualist triumphs: things appear at you -- ridiculously clunky handmades and hand-me-downs, what thrills in their appearance is precisely their undeniably transient appearance. (Yes, that's probably why polarized 3-D's used mostly for sex, but the match to spiritualism's even more uncanny.) "Its light roupagem allowed that the beautiful azeitonada color of its neck, the shoulders, the arms and the ankles was seen very well. The long black and wavy hair went down for the shoulders until below of the chest and were tied by a species of teeny turban. Its feições were small, correct and gracious; the eyes were black, great and livings creature; all its movements were full of those infantile favours or as of a young gazela, when vi, shy and the determined one, among the curtains." "The most convincing bio-pic since Man Ray, Man Ray!" |

|

| . . . 2001-01-26 |

|

The writer of my favorite single poem of the past five years is unknown, but all that really matters in the Digital Millenium is the property owner -- and, fortunately for us, that owner is Juliet Clark. We thank her for her generous donation. |

| . . . 2001-02-16 |

From Synthetic Zero:

"I recall reading a story about a foreigner who was in Tokyo during one of the firebombings, and these Japanese women were watching the fires and explosions from the window of their paper house. And so they exclaimed, 'kirei-na!' (how pretty!) It's not that they were airheads who didn't know what was happening to them, but the Japanese attitude about such things is that one should accept even the worst disaster as what it is --- because there's no point in pretending or hoping it isn't happening when it manifestly is."

I remember when I was a holier-than-thou kid struggling with my reaction to aestheticized horror (which holier-than-thou Christianity offers in plenty but with monopolistic intent) -- like a dog cringing because it imagined killing a sheep. And I guess I still sometimes find myself having to consciously work out these distinctions....

I remember when I was a holier-than-thou kid struggling with my reaction to aestheticized horror (which holier-than-thou Christianity offers in plenty but with monopolistic intent) -- like a dog cringing because it imagined killing a sheep. And I guess I still sometimes find myself having to consciously work out these distinctions....

The consequences of aesthetic/ethical confusion aren't always so passive. Like when working or semi-pro artists get into the habit of producing new real-life horrors just so's to have another opportunity to represent them. Mainstream American poetry might think it's redeeming horrific experience; to me it looks more like it's rhetoricizing self-righteousness and a rather toothless remorse, both of 'em easily replenishable resources.

So I gotta disagree with Geegaw's saying William Logan's latest hissy fit "is all wrong": it's right that the hissed-at poets are overrated (insofar as poets get any ratings) and that the quoted poetry stinks. But explaining why it stinks, that's where things fall apart. When a currency's so debased that the only people who care about it are forgers and numismatists, critical judgment comes down to stuff like "It's heavy and shiny!" or "This doesn't match the rest of my collection!" And when Logan wants to balance antagonism with some grudging praise, he proffers the Sax-Rohmeresque:

... In the town centerI agree with Logan that these are "memorable lines": "Did you hear me? BABY DUCKS!" But he also calls them "direct and discomforting" instead of "hilarious bathos," so I don't think I'll be going on a shopping spree any time soon....

of Kwangju, there was a late October market fair.

Some guy was barbecuing halfs of baby chicks on a long, sooty contraption

of a grill, slathering them with soy sauce.

Baby chicks.

| . . . 2001-04-16 |

| Our Motto: | (via June Brigman & Mary Schmich) |

| |

|

What with nostalgia for when I had more writing time and anticipating when I'll have it again and too many dampened spirits among my compeers and maybe even a trace of Joey Ramone sentiment, I feel like expressing less sheepishness than usual about these web ventures. Although deciding that one's desire is deserving of respect probably fulfills some nutritional need or another, audience members with weaker stomachs may wish to turn away.

Yeah, as another asshole said in the catchiest phrase he'll ever coin, occasional writings are advertisements for oneself. But the reason so many of my treasured friends write well is because they're also advertising something better than just self: curiosity, engagement, humor, anti-solipsistic passion.... It's possible to attract attention for a worthwhile purpose, like mutual satisfaction. And yeah, the web is vanity publishing. But it's not only vanity: it's also an attempt to add to the evidence that love is other than career. If that's hubristic, at least it's in a tradition of not particularly destructive hubris: Virtually every piece of critical writing I care about came from "amateurs," and quite a bit of the art as well. As a reward for being an amateur at a time when the persistent and cheap publishing medium of the web is available, I get a heartening number of responses from working students and from working artists (although only once from a working academic, I wonder why) -- but the beauty of amateurism is that by definition numbers don't matter. The success of a marriage doesn't depend on how many priests attend the wedding. So, at Juliet Clark's suggestion (she's been reading E. B. White's wartime essays about his small egg-and-dairy farm), I'm going to stop using all those more unpleasant names and start calling myself a "gentleman critic." |

| . . . 2001-04-28 |

East Bay Dining: Caffe Mediterraneum

The only "Med" thing about the Caffe Med is the state of its toilet -- a little slice of Brindisi right in Berkeley!

Recently, while reminiscing over a fine scotch at the Club, international troubleshooter Juliet Clark told us of her most treasured Caffe Med moment. Trying to distract herself from other sensory input by reading through the typically-Telegraph-Ave. graffiti, she found in very neat very tiny ballpoint pen the message:

That was ten years ago and she's never been back.

| . . . 2001-05-06 |

I started reading Derrida immediately after taking a class on Nagarjuna's masterwork, Codependent No More. It's always pleasant to fantasize that autobiographical accident somehow counts as critical insight, and so my rolling bloodshot eyes paused over Curtis White's latest confident assertion:

Anyone who has taken the trouble to understand Derrida will tell you that this putative incoherence was the discovery that the possibility for the Western metaphysics of presence was dependent on its impossibility, an insight that Derrida shared with Nietzsche, Hegel, and the Buddhist philosopher of sunyata, Nagarjuna, who wrote that being was emptiness and that emptiness was empty too.And I don't care much what club is used to belabor Harold Bloom so long as he gets lumpier.... But White's unadorned Adorno is not much more palatable:

"Aesthetic experience is not genuine experience unless it becomes philosophy."An ambitious mission if taken seriously, but a terrible guide if taken as Adorno does (i.e., "Art that is not easily explained by my philosophy does not count as art" -- if Adorno was doing philosophy of math, he'd declare that 5 wasn't an integer because it's not divisible by two). Aesthetics is empirical philosophy, and if pursued without attention to particulars, you quickly end up with nonsense like using a single-dimensional scale of "complexity" to ascertain "greatness." (Scientific attempts at researching "complexity" make for amusing reading, given the muddling ambiguity that attentiveness brings in, and the inevitable toppling over of increasing perceived complexity either into perceived organizational structure -- i.e., greater simplicity -- or into perceived noise -- i.e., greater simplicity.)

More pernicious, and indicative of why smart lads like Derrida avoid the whole question of "greatness," is White's contrast of a "simple folk tune" with what "a Bach or Beethoven will then make of this tune," the former being prima facie non-great and the latter being great. Note the indefinite article: we're now so far from particulars that we're not even sure how many Bachs or Beethovens there are.

And note the isolation of the tune, floating in space, divorced from performer or listener: no wonder the poor thing is simple. Why doesn't White contrast "a simple folk singer" with "a Beethoven" instead? How about with "an Aaron Copland"? Or with "a John Williams"? Is Skip James's 1964 studio performance of "Crow Jane" less complex and therefore less great than a slogging performance of an aria from "Fidelio"? How about if the former is given close attention and the latter only cursory? Is study of a printed orchestral score somehow more aesthetically valid a response to music than, say, dancing?

I'm pretty sure how Adorno would answer all those questions, to give the dickens his due. White, I think, would rather avoid them.

I owe 'im, though, for providing the following lovely quote from Viktor Shklovsky, which for some reason makes me think of The Butterfly Murders:

"Automization eats away at things, at clothes, at furniture, at our wives, and at our fear of war."

| . . . 2001-05-13 |

The Blasted Stumps of Academe

Lawrence L. White simultaneously kicks off our end-of-school special and continues our previous thread in high style:

|

|

| . . . 2001-06-07 |

On May 16, 2001, Ruthie's Double pointed out that online serial publishing is subject to the same sort of fallacious interpretation as online advertising. Rather than deal with the shock of the uniquely accurate evidence of viewer engagement that web monitoring allows, advertisers and blockbustin' authors prefer to retreat to their established fantasy worlds -- after all, they couldn't be so rich if they weren't so right....

It's conceivable that way less than 75% of the people who read his traditional print books actually pay for the experience. They borrow the book from friends, check it out from public libraries, etc....It's as if the first Nielsen ratings resulted in all the television networks shutting down in a fit of pique.There's no statistics as to how many people purchase, but stop reading Stephen King's books after the first chapter (I know I probably would). Perhaps the people who paid for the first chapter had stopped feeling like it was worthwhile to pay until the story got better....

| . . . 2001-07-04 |

Declaration of Dependence

Even the most attentive reader will have failed to discover one of those near-ubiquitous "other weblogs" sidebars in the Hotsy Totsy Club, but that's not because I'm a Mister Stuck-Up Patootie McSnoob. On the contrary, I love all the crazy kids in our impressively scatterbrained new genre. It's just there's no room for sidebars in a dive like this: individual entries assume a formatting freedom which precludes a page-high multi-column layout.

Since I'm currently engaged in a couple of more extended projects (a tribute to Son of Paleface, a "reading edition" of George Gascoigne's autobiographical novel, and an essay on Jean Eustache), let's celebrate the Club's second anniversary and my lapse of attention with an Other Weblogs Fullbar:

Manual: allaboutgeorge - Ancient World - Arts Journal - blort - Bovine Inversus - BradLands - Brain Dump - clinkclank - ComicGeek.CA - Dagmar Chili - daily dean - Dancing Sausage - dangerousmeta - DrMike - Eclogues - feminist media watch - grim amusements - Gus - Honeyguide - JimWich - John Saleeby - Lines & Splines - Making Light - markpasc - METAEZINE - metameat - Neat New - NewsTrolls - NextDraft - NQPaOFU - Obscure Store - Open Brackets - Pumpkin Publog - s. kamau mucoki - Splinters - Timothompson - Tomato Nation - Unknown News - Usability Weblog - World New York

| . . . 2001-07-18 |

Added today to our Bellona Times Repress line: a reading edition of The Adventures of Master F. J. by George Gascoigne, with introductory remarks and notes on the 1575 revision.

"In 1573, George Gascoigne published the first autobiographical novel in English...."

| . . . 2001-09-12 |

Our Education President

"In Florida, Bush was reading to children in a classroom at 9:05 a.m. when his chief of staff, Andrew Card, whispered into his ear. The president briefly turned somber before he resumed reading. He addressed the tragedy about a half-hour later."(More substantial slices of soon-to-be-erased history are collected at Ethel.)

| . . . 2001-09-17 |

After reading the explanation (via Media News), I'm still unable to understand how a newspaper editor (or two, if you count the Village Voice) decided that the most appropriate headline for a story about hijackings, the murder of thousands, a successful attack on the Pentagon, and the destruction of the World Trade Center would be the single word "BASTARDS!". Maybe I'm just not big-paper material, but on Tuesday night my mood would've been better expressed as "HELP!"

When the front page was unfolded, it looked like the burning towers were the targets of the slur. Folded, whenever it startled me from a vending machine, I felt exhorted towards a rally for us born-out-of-wedlocks -- or like I was being pointed out to an angry mob. (I assure you that my people are a peaceful people, and many of us are even American citizens.)

Even on what I presume were its own terms of impotent bluster, the headline was misleading, since, as it turned out, the reporters had no idea just who the bastards were. It's like headlining your post-election paper with "PRESIDENT!" and never mentioning the winner's name on the pages within.

| . . . 2001-09-27 |

|

Nowadays there's a lot more of that going around, but it still seems worth bringing up. Flag-waving (link via Electrolite) is an easy and transient exercise; worthier of scrutiny are less strictly symbolic acts, such as legislation. Our current national leaders have a history of opportunism, and they've been handed a splendid opportunity.

No one's really bothered to pick it up yet, but over the past two decades, right-wing Republicans have had to discard what used to be one of their favorite political weapons: patriotism. (A narrow form of xenophobia is still wielded in especially racist states such as California, but America, being a nation of immigrants, doesn't lend itself to ethnically-based nationalism.)

In the 1950s and 1960s, conservative Republicans were able to push the patriotism button pretty heavily. Left-of-liberals muddied domestic waters by dopey idealization of the Soviet Union or China, southern Democrats still saluted nothing but Dixie, and opposition to government involvement in Vietnam easily slued into attacks on the military itself.

Well, there are essentially no more left-of-liberals, no one outside the executive suite has much good to say for China, the military budget has been devoted to frivolous weapons research while ignoring personnel, and the dominant wing of the Republican party doesn't have a red, white, and blue pot to piss in.

Reaganesque anti-federal propaganda brought a plague of do-nothings who move into political office on corporate support, interfere with or dismantle useful services, re-route tax money to corporations, and then move back into cushy corporate positions. (I might not exactly enjoy the thought of sewage, but that doesn't make me want to hire a high-priced plumber to remove all the pipes.) Their allegiances are pledged to two special interest groups:

"Big-spending" "bleeding-heart" liberals, by definition, believe that the American system of government is good and capable, that the American people are worthy of defense and respect, and that America can be both a haven and a promise of limitless possibilities. That gives them access to a heap of rhetorical tools that've proven very useful in the past, and which might as well get used.

| . . . 2001-09-29 |

Essays We Never Bothered Finishing Dept.

|

It's weird but I actually do seem to remember James Thurber -- it's Taylor Antrim that I'm having trouble placing....

| . . . 2001-10-10 |

At the doctor's office yesterday (it's been a busy week here), I saw a poster with a dozen cute little cartoons of the Warning Signs of Diabetes. "Excessive Hunger" was a guy shoving a cake into his mouth, "Sexual Dysfunction" was an sad-faced man lying in bed with a sad-faced woman, and so on. But "Vaginal Infection" was a woman holding a sign in front of her torso that read "Vaginal Infection." That is to say that the warning sign of a vaginal infection is literally a "Vaginal Infection" warning sign.

Maybe this is only interesting if you're reading Wittgenstein....

| . . . 2001-10-12 |

As Jean Teasdale has pointed out, "we should pursue the distractions that make our lives fulfilling and worthwhile, because life is not about getting angry over things you cannot control, but pleasing yourself."

It is thus my duty to report that the September 1959 issue of Coronet that supplied today's cover girl also contained many disturbing exploitive photographs of not-quite-sixteen Tuesday Weld: bookish, anguished, winning, odd, painting, and reading.

| . . . 2001-10-14 |

The Indefinite Conversation

A reader either cheers me on or lumps me in, I can't tell which:

| what breed of idiots |

Which reminds me again how hard it is to keep that greased-piglet of a "we" out of political discourse, and how painful it is to recall that the nested affiliations "a couple of webloggers who read each other," "liberals who read anything," "the American voting public," and "global humanity" are not precisely interchangeable. For example, the first group in that list -- and possibly the second as well -- is easily outnumbered by the group of "people who decide how to vote based on TV commercials." (After which, to be sure, we all collectively enjoy the results.)

Colette Lise joins a particularly exclusive community of shared trauma:

| That Warning Signs of Diabetes thing is in my doctor's office, too. Creepy. Why are you reading Wittgenstein? |

| I have a toothache. |

Or at least everyone is moaning. And why else would they moan?

| But if here we talk of perversity, we might also assume that we all were perverse. For how are we, or B, ever to find out that he is perverse?

The idea is, that he finds out (and we do) when later on he learns how the word 'perverse' is used and then he remembers that he was that way all along. |

|

| - Ludwig Wittgenstein, "Notes for Lectures on 'Toothache' and 'Toothache'," Philosophical Occasions | |

| . . . 2001-10-16 |

The Indefinite Conversation, cont.

Reader Toadex Hobogrammathon directs our attention to the welcome subject of to rojec tmy ergnaoreys:

| thro yr Ardent urgency, have I can come to Z; accidental Ctrl-b, close window, I wrote a something to Ray, ... ;;;; What may I be writing an Rutgersial anthological comment on Zukofsky, do yo have any bookings to recomment,?? Or articles?? Are you attributed to him? I mean, I'm drafted by class, to write by an anthology of Rutgers, what Z did and said, and so forth. I got a goddamn refridgerator the last guy had to assault me with some whirr less than buzzing, when one dranks enough to listen. And before a four days ago, I didnaot know tha te emoeuseic of A24 is H via C, so enough of tracking up and through the left, good days to you and thakn yuo of all the |

Louis Zukofsky was a man, and a big man. Killed him a bar when he was only three, climbed up a mountain without skinning his knee, wrote naw-thing lak po-ee try, and brought home a baby bumblebee. Zukofsky is a legend of the West.

Past these basic facts, the most reliable biographical source I've found is the ever-charming Kevin Killian:

| I remember being

furious and moping around my parents' house when Time magazine said Frank

O'Hara had been killed by a dune buggy on Fire Island.

I was very pouty for weeks & my dad said, "Why don't you write to Louis Zukofsky?" I perkled up & asked him who he was. He didn't really know, but LZ had been on the same TV program (NET) that O'Hara was. "And plus," he said, "he lives in Port Jefferson. And he's always writing letters to the editor" [of our nearby paper, The Port Jefferson "Record"] - "complaining about this or that." Well I got on my bike, I was like 13 or 14, and headed to Port Jefferson which was about 10 miles away and went to the house of Louis Zukofsky. He would always write letters to the paper about traffic in front of his house, etc. He was not happy to see me - I don't think he cared for school children. I was about 13. He was a mean curmudgeon, but the garden was beautiful to my eyes. I resolved as soon as I was old enough to get a drivers license, to take a big station wagon and drive right through his hedges, in the middle of the night. I think my brief encounter with Zukofsky colored the rest of my reading of him, ever since. "99 Flowers" indeed! He wouldn't have had 1 flower left if I had had my way! Luckily my childhood anger faded by the time I was 15 or so and started to drive. I didn't meet any other poets until I was about 17 and met Paul Blackburn in New York. But Alex Haley did come to our classroom & told us all about writing the "Autobiography of Malcolm X." I'm reading this over & I'm, like, stunned at how stupid I sound. |

More insight from Killian: "Louis: Harry Dean Stanton. Celia: Kate Nelligan. Paul: Macaulay Culkin."

| . . . 2001-11-04 |

The blurb is a difficult form at best, but its authors risk especial injury when they wrap a subject as prickly as Thomas Bernhard, whose pinched sneer -- more vitreous than vitriolic, less sulphurous than hydrogen-sulfidic -- casts a consistently unflattering (if dim) light on all around it. (And on itself as well; it seemed to me that Woodcutters would've worked better if the narrator's scornful scare-italics had slowly increased their share of the prose until they covered every word he set down....)

The most amusing page of Woodcutters (and for pity's sake I'll skip the introductory sentence which blows the joke) is the nearly Flaubertian (first draft Flaubert, anyway):

| To present The Wild Duck to the Viennese public was not just a risk, said the actor, but a considerable gamble. The Viennese simply did not respond to modern drama, as he put it -- they never had responded to modern drama. They preferred to go and see classical plays, and The Wild Duck was not a classical play -- it was a modern play, which might admittedly one day become a classic. Ibsen might one day join the classics, and so might Strindberg, said the actor. He had often felt that Strindberg was a greater dramatist than Ibsen. Yet at other times, he said, I've felt the opposite to be true -- that Ibsen is superior to Strindberg and has a better prospect of becoming a classic. Sometimes I think Miss Julie will one day become a classic, and at other times I think it'll be a play like The Wild Duck. But if we attach too much importance to Strindberg we do Ibsen an injustice, he said, just as we do Strindberg an injustice if we attach too much importance to Ibsen. Personally, he said, he loved the Nordic way of writing, the Nordic way of writing for the theater. He had always loved Edvard Munch too. I've always loved The Cry, he said -- which of course you are all familiar with. What an extraordinary work of art! I once went to Oslo just to see The Cry, when it was still in Oslo. That doesn't mean that I have a preference for the Scandinavian countries, he said. Whenever I was in Scandinavia I had a nostalgia for the south, or at least for Germany, he said. Stockholm -- what a dreary city! To say nothing of Oslo -- so enervating, so soul-destroying. And Copenhagen -- enough said! |

But the second most amusing page is the back cover:

|

"Mr. Bernhard's portrait of a society in dissolution has a Scandinavian darkness reminiscent of Ibsen and Strindberg...." -- Mark Anderson, New York Times Book Review |

| . . . 2001-11-20 |

|

Last week, Paul McEnery bemoaned to me the balkanized states of psychology in America: clinical psychologists ignoring research psychologists ignoring social psychologists when they could so profitably be building on each others' work....

As a layperson who likes snooping around half-understood academic journals, I've wondered about that myself.

For example, when reading a very widely noted report (Joan Freeman knows how to work those publicity machines!) that "emotional problems" and "mundane jobs" are more likely to come to intelligent children who are told they're gifted than to those "told nothing."

"Told nothing"? Enticingly vague, that....

Thus enticed toward a fuller summary, I find that Freeman's study "compared [after 27 years] the lives of pupils whose parents joined a society for gifted children with equally talented students whose parents were not members."

OK, then, what Freeman compared wasn't "children told all" vs. "children told nothing," but "parents who joined a society" vs. "parents who didn't join."

As Freeman herself acknowledges, high-IQ children are more likely to be singled out for special treatment if they already have behavior problems. Otherwise, they'll just be getting along quietly (and easily) in school. (It wasn't teaching myself to read that attracted my guardians' attention; it was acting like a horrid little monster in kindergarten. Only as part of trying to figure out how to calm me the fuck down did a counselor come up with the "gifted" label -- which may well mean that my sole "gift" was that of acting like a horrid little monster. "And what super powers do you have?") Right off, that skews the study to a "gifted" / "disturbed" correlation.

Then there's the question of what kind of parent would be most likely to join the society. Seems likely it would be someone worried about freakiness or about class mobility, either of which would up the tensions at home. As opposed to, like, all the smart-as-a-whip people I met later who came from families where big IQs weren't considered big deals: bohemian or genteelly academic or upper-middle-class or just amazing.

And it seems unlikely that society membership would be felt necessary if there was an obvious route already laid out for the kid -- something like the Bronx High School of Science or the Dalton School, where academic progress wouldn't require a misaligned age -- as opposed to having to decide between jumping grades in a regular old underfunded public school or staying stuck in a regular old underfunded public school.

Freeman's results may be secure as all get-out, then, but their only clear application is "don't think that joining a society for gifted children is going to be helpful for your child." They certainly don't support Freeman's extensive lists of recommendations, some of which seem benign -- don't assume the kid can make mature decisions -- but some of which seem less than realistic. (Despite the lasting inconveniences of that kindergarten badge, I'd have to insist that the most genuinely cheery times I had in school were due to the singling-out counselors and the few teachers not too exhausted to handle special-tracking -- though I still cringe remembering the agonizing opacity of fractions.)

Population studies work fine for spotting problems, but for spotting causes and treatments you can't beat lab work. Such as Mueller & Dweck's 1998 study showing that praise for intelligence or giftedness mimics learned helplessness, lowering both performance and motivation, whereas praise for effort or for the task itself increases performance and motivation.

Mueller & Dweck admitted their study's limits, but it ties usefully into other research, like Dykman's. And they also came up with plausible empathic explanations for the results: My attention having been drawn to myself, my goal becomes maintenance of my self-image by "succeeding at" the task, a starkly win-or-lose approach which hardly entices me to move forward: winning means I'm done, and losing means I lack the innate ability I thought I had. More fruitful is to define the goal as gradually improved competence, with setbacks expected and due to (surmountable) lack of effort or training.

(And, as a "To Be Continued" marker, their contrast of inward and outward attentiveness fits some central neuraesthetic speculations....)

| . . . 2001-12-22 |

By writing out a puzzle, Lawrence L. White finds the solution (and as a side-effect shares it):

In the latest issue of Context a piece on Kathy Acker brought to mind an old problem.Ms. Wheeler talks a lot about Acker's ambitions (to change the world w/words) but not much about how she carried it out. & the ambitions are read straight off. Any clever workshop student knows "show, don't tell," and, as Marx put it, "every shopkeeper can distinguish between what somebody professes to be and he really is."

To be fair, there's a lot to say about stated intentions. You can at least repeat them. There may not be that much to say about the means art uses. & of the little that has been said, most of it is painfully obvious. But maybe that's okeh. Maybe there should be less talking about poems & more reading them.

Then I noticed how I had not managed to avoid my own problem. Wittgenstein says, somewhere, something like what is needed is not new theories but reminders of what we wanted to do in the first place. So reminding yourself which problems are bothering you might not be a complete waste of time.

Better yet, why not make talk about poems as interesting as the most interesting poems?

| . . . 2002-03-20 |

The English Restoration seems startlingly close, as if a veil was lifted for a few decades and then hurriedly pulled back into place for two hundred more years. Generations of state-church tussling, civil war, and dictatorship had left England a fragmented culture bound together by a tradition of insecurity, uncertainty, and paranoia. Installation of the most tolerant monarch in its history unloosed a flood of free expression: of sexual pleasures and horrors, atheism and fanaticism, financial panic and soured idealism, class distinctions crossed and fetishized, free love and cheating at cards....

All very twentieth century save for the lack of whining. Among Restoration writers, hypocrisy and self-pity were more unforgivable than failure or disgrace, since, after all, failure and disgrace lay so clearly outside an individual's control. Most valued was a slantwise directness of insight and impulse, coupled with a humorously stoic awareness of the probable consequences.

Although newspapers, novels, and television weren't yet in full swing, many other aspects of modernity snapped into focus: science blossomed free of alchemy and astrology; for the first time, women wrote professionally (including all-round woman-of-letters Aphra Behn); diaries and letters and memoirs suddenly became compulsively readable narratives rather than bare inventories of purchases or devotions; William Congreve's comedies (largely predicated on their young heroes' fears of bankruptcy) remain the best in the English language; John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, remains the most exfoliative of English poets.

For reasons we won't go into, the Victorian era offered little open support to its Restoration forebears, and into the mid-twentieth century much material was more or less supressed. Congreve stayed in print, though, and at present the writings of Pepys, Rochester, and the Female Wits are probably more accessible than ever before. But one of my favorite Restoration relics has never quite recovered its former visibility, and so I decided to produce an online edition.

For reasons we won't go into, the Victorian era offered little open support to its Restoration forebears, and into the mid-twentieth century much material was more or less supressed. Congreve stayed in print, though, and at present the writings of Pepys, Rochester, and the Female Wits are probably more accessible than ever before. But one of my favorite Restoration relics has never quite recovered its former visibility, and so I decided to produce an online edition.

|

Now Heav'ns preserve our faith's defender From Paris plots and Roman cunt, From Mazarine, that new Pretender, And from that politique, Grammont. -- John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester |

The memoirs of the Count de Grammont were written in French, but I associate them with the English Restoration since they were ghostwritten by Anglo-Irish Anthony Hamilton, since (apart from some short introductory chapters) they're set entirely in the court of Charles II, and since, most germanely, I know them through a remarkable nineteenth-century English edition aimed at the Sophisticated Gentleman.

As I've mentioned before, it's one of my favorite books, largely due to its internal linkage. But I'm finding it a bit intractable to both online publishing and online reading: luxuriant sentence structure, multipage paragraphs, and gargantuan notes all work more efficiently in paper technology than in computer hypertext, and the tiny none-too-tidy print clogs OCR.

A bit at a time seems the best way to proceed. And so, contrary to my previous practice, I'll be issuing the Memoirs in serial fashion.

Of this initial installment, I actually slighly prefer the bizarre Victorian wrapping to the contents proper, although Hamilton's declaration of methodology, Grammont's Sgt.-Bilko-like account of seventeenth-century warfare, and his easy socializing with both king and rebel during an armed rebellion all hold their charms.

Next in the hopper, though, is his introduction to the English court, and then we'll be cooking with gas!

| . . . 2002-05-03 |

Neuraesthetics: Foundations, cont.

|

It's inherent to the mind's workings that we'll always be blinded and bound by our own techniques.

Another example of this -- which actually bugs me even more than ancient Egyptians taking brains out of mummies -- is when essayists or philosophers or cognitive scientists or divorced alcoholic libertarians or other dealers in argumentative prose express confusion (whether positive or negative) before the very existence of art, or fantasy, or even of emotion -- you know, mushy gooey stuff. Sometimes they're weirdly condescending, sometimes they're weirdly idealizing, and sometimes, in the great tradition of such dichotomies, they seem able to, at a glance, categorize each example as either a transcendent mystery (e.g., "Mozart," "love") or a noxious byproduct (e.g., "popular music," "lust").

| (Should you need a few quick examples, there are some bumping in the blimp-filled breeze at Edge.org -- "Why do people like music?", "Why do we tell stories?", "Why do we decorate?" -- a shallow-answers-to-snappy-questions formula that lets me revisit, through the miracle of the world-wide web, the stunned awful feeling I had as a child after I tackled the Great Books Syntopicon....) |

These dedicated thinkers somehow don't notice, even when they're trying to redirect their attention, what they must already know very well from intellectual history and developmental psychology both: that their technique is blatantly dependent on what seems mysteriously useless to the technique.

Cognition doesn't exist without effort, and so emotional affect is essential to getting cognition done. Just listen to their raised or swallowed, cracked or purring voices: you'll seldom find anyone more patently overwhelmed by pleasure or anger or resentment than a "rationalist," which is one reason we rationalists so often lose debates with comfortably dogmatic morons.

Similarly, "purely observational" empiricism or logic could only produce a sedately muffled version of blooming buzzing confusion -- would only be, in fact, meditation. Interviews, memoirs, and psych lab experiments all indicate that scientists and mathematicians, whether students or professionals, start their work by looking for patterns. Which they then try to represent using the rules of their chosen games (some of the rules being more obviously arbitrary than others). And they know they're done with their new piece when they've managed to find satisfying patterns in the results. It's not that truth is beauty so much as that truth-seekers are driven by aesthetic motives. ("It's easier to admit that there's a difference between boring and false than that there's a difference between interesting and true.")

Studies in experimental psychology indicate that deductive logic (as opposed to strictly empirical reasoning) is impossible without the ability to explicitly engage in fantasy: one has to be able to pretend in what one doesn't really believe to be able to work out the rules of "if this, then that" reasoning. The standard Piaget research on developmental psychology says that most children are unable to fully handle logical problems until they're twelve or so. But even two-year-olds can work out syllogisms if they're told that it's make-believe.

Rationality itself doesn't just pop out of our foreheads solitary and fully armed: it's the child of rhetoric. Only through the process of argument and comparison and mutual conviction do people ever (if ever) come to agree that mathematics and logic are those rhetorical techniques and descriptive tools that have turned out to be inarguable. (Which is why they can seem magical or divine to extremely argumentative people like the ancient Greeks: It's omnipotence! ...at arguing!)

An argument is a sequence of statements that makes a whole; it has a plot, with a beginning, a middle, and an end. And so rhetoric is, in turn, dependent on having learned the techniques of narrative: "It was his story against mine, but I told my story better."

As for narrative.... We have perception and we have memory: things change. To deal with that, we need to incorporate change itself into a new more stable concept. (When young children tell stories, they usually take a very direct route from stability back to initial stability: there's a setup, then there's some misfortune, then some action is taken, and the status quo is restored. There's little to no mention of motivation, but heavy reliance on visual description and on physically mimicking the action, with plenty of reassurances that "this is just a story." Story = Change - Change.)

And then to be able to communicate, we need to learn to turn the new concept into a publicly acceptable artifact. "Cat" can be taught by pointing to cats, but notions like past tense and causality can only be taught and expressed with narrative.

It seems clear enough that the aesthetic impulse -- the impulse to differentiate objects by messing around with them and to create new objects and then mess around with them -- is a starting point for most of what we define as mind. (Descartes creates thoughts and therefore creates a creator of those thoughts.)

So there's no mystery as to why people make music and make narrative. People are artifact-makers who experience the dimension of time. And music and narrative are how you make artifacts with a temporal dimension.

Rational argument? That's just gravy. Mmmm... delicious gravy....

|

Further reading

I delivered something much like the above, except with even less grammar and even more whooping and hollering, as the first part of last week's lecture. Oddly, since then on the web there's been an outbreak of commentary regarding the extent to which narrative and rationality play Poitier-and-Curtis. Well, by "outbreak" I guess I just mean two links I hadn't seen before, but that's still more zeitgeist than I'm accustomed to.

|

| . . . 2002-06-16 |

Papa Was a Wandering Rock

One of the odd aspects of Finnegans Wake -- maybe because it's such a well-established limit case -- is the difficulty of making any statement about it that's not equally applicable to every other literary work:

|

For Schmidt, in "Der Triton," establishing a reading model is essential to dealing with the Wake.... I, for my part, would like to contradict both Reichert and Schmidt: if one wants to translate, one has strictly to avoid any reading model, any interpretation of what is going on in Finnegans Wake. The translator has to understand nothing. He or she has to look at Joyce's text with as little understanding as possible and to translate Joyce's sentences into sentences that the translator does not understand either.

What I am talking about is not the "tricky problem" referred to by members of the Franfurt Wake group of "how to translate those words that one simply does not understand." Of course, I would like to "understand" every single word -- or, to be more precise, to "understand" what is present in a single word and a given sentence, but, as translator, I do not need to understand why it is present there. Basically, this is the difference between shape and meaning, between knowledge and understanding: the ideal translator of Finnegans Wake knows everything about the text but understands nothing.... On the other hand, the Schmidtian translator -- the one who believes that he or she understands something because of having a reading model -- must inevitably establish a different kind of hierarchy: the one between information that is understood and information that is not understood; between information that supports a reading model and information that does not; between what is felt to be important in Joyce's text and what is felt to be unimportant (or even disturbing). It is obvious that this translator will translate the hierarchy that she or she has established in the text but not the nonhierarchical text that every reader has a claim to.... |

| -- "Sprakin sea Djoytsch?: Finnegans Wake into German" by Friedhelm Rathjen, James Joyce Quarterly Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 905-916 |

| . . . 2002-06-21 |

|

The Arizonian is a wonderful anomaly: a 1930s Western B-movie that scrapes the mindless sunny-side-up of Buck Jones or Gene Autry into the slops and rustles us up something more like Marxist spaghetti or the bitter winter rye of Joseph H. Lewis.

There's no roving outlaw gang or renegade Injuns; instead, all hell boils over due to departmental rivalry between marshal, sheriff, and mayor, and the intertwining of money and politics (brought together, as ever, in the person of Louis Calhern). Ethical and emotional compromise is frequent, and sporadically effective at delaying the progression from bullying to murder to group ambushes to massacre. Costumes, sets, and lighting all have a worked-over and lived-in look. So does hero Richard Dix, who carries the gravitas of Randolph-Scott-on-Jupiter -- he's even stolidly tragic about getting the girl.

Where the movie doesn't -- for the most part -- rise above its station is in its "comic relief." With scare quotes because it's scary. When it comes to inspiring utter shamefaced horror in post-Jim-Crow audiences, shuffling idiot Willie Best is second only to the sub-Tor-ean Fred "Snowflake" Toones. Best may be the only guy who can really make us appreciate the skill of Stepin Fetchit. (Mantan Moreland and Eddie "Rochester" Anderson are in another class altogether -- those guys were stars.) But wait, there's more! Much more, by volume anyway: Best's "comic relief" "love" interest in the film is Etta McDaniel, the lookalike but much less talented sister of Hattie McDaniel.

So.... The most I can say is that at least white actors weren't being paid to wear the blackface.

But even here the movie holds a surprise if you can get past "the most part." [And if you want to keep it a surprise, stop reading -- but I reckon odds are slim that any of you will get a chance to see it soon.] The film's everything-falls-apart catastrophe begins with the shooting of Willie Best, rather than, I don't know, the love interest of the hero? a drunk newspaper editor?

Then the allies, having arranged a cover of total blankness, walk into total blankness, firing, disappearing. As the smoke clears, the one true melancholy hero stands alone, surrounded by corpses. Making the perfect target for the one true self-assured villain.

Who in turn turns out to make the perfect target for Hattie McDaniel's sister.

A lunatic servant saves the world with a shot in the back. This is a most satisfying conclusion to the sort of story that's being told.

But that's because it's a disturbingly odd conclusion.

The American Film Institute catalog was disturbed enough to repress the memory entirely. Etta McDaniel, despite her surprisingly central role, doesn't get mentioned in the movie's credits. That sort of omission's not unusual in a 1930s B-picture. But it is unusual for the AFI researcher to have not filled that credit in, and then to have simplified the ending to: "The only survivor of the gun battle, Clay leaves a reformed Silver City with Kitty at his side."

After the catalog was printed, the AFI was apparently told that there was a problem and someone tried to correct it on their super-expensive-exclusive-access-only web site. That someone hadn't bothered to see the first hour of the movie, though, because their correction goes as follows: "... a mysterious black woman [who's been in about a half-dozen earlier scenes] shoots Mannen with a rifle."

(A more accurately chaotic synopsis is available online. I'd send a correction to the AFI's web site but they don't give any contact information.)