|

||

| . . . Chronicles . . . Topics . . . Repress . . . RSS . . . Loglist . . . | ||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| . . . 2021-06-06 | ||||||

But I never forgot the look of astonishment and bewilderment on the young woman's face when I had finished reading and glanced at her. Her inability to grasp what I had done or was trying to do somehow gratified me. Afterwards whenever I thought of her reaction I smiled happily for some unaccountable reason.- Black Boy by Richard Wright

| . . . 2021-06-16 |

- for David Collard, with gratitude

"W. N. P. Barbellion" claimed instant fellowship with (what he lived long enough to read of) James Joyce. They shared pride and poverty, compulsive truth-telling, retreats into silence, and a sense of exile.

More particularly they were both intellectually ambitious provincials stuck on the periphery of longue durée cultural shifts.

Bruce Cummings was born to be a naturalist in the grand old tradition, devoting his passions and skills to the present-to-hand reality of plants, beasts, and earth on the ground. He should've sailed on the Beagle or explicated the ecology of the English countryside, but such escapades had already become a gentleman-scholar's game and would soon become the niche of pop-science writers like Barbellion's champion H. G. Wells. "Real" working-class science instead took place in urban offices and urban labs for the greater profit of industry or government.

Although I sense a leap in energy and happiness whenever Cummings returned to the countryside, he never himself described that dichotomy in so many words. Instead, like other brilliant articulate failures, he redirected himself from his first vocation to literature. He would still observe, analyze, and describe, but specimens would be human and he would be first on the dissection table.

James Joyce faced similar blockages but his vocations were spiritual and literary from the start, and due to whatever combination of history, capability, and opportunity Joyce became more explicitly aware of his dilemma, formed vaster ambitions, and lived to fulfill them.

We have no way to know where Cummings would've gone next, or if he would have been able to publish even one book without the sales hook of his early death. On the other hand, would Joyce be remembered if he'd died at Cummings's age, with only Chamber Music to his name? At the very least, Cummings's publications provide a unique testament of Dedalus-in-progress, drowned before flight, as I reckon most members of the extended Dedalus clan have been.

More particularly still, they share a certain attitude.

Embodied/embedded/naturalist philosophers and scientists, much as I love 'em, often speak of human experience in ways which would (thoughtlessly for the most part, sincerely for the horrifying part) dismiss the blind, the deaf, the pained, the frail, the immobilized, the illiterate, or the starving as not-really-human. (Other philosophers seem willing to dismiss any non-philosopher, no matter what shape they're in, as subhuman, so it may just come with the territory.) Those philosophers, theologians, and mystics who do admit the existence of suffering also tend to deny the existence of anything else, with sweet nothing our only transcendence.

In literature there's a minor muscular-secular-hedonist tradition, viz. that hearty medico buck Oliver Gogarty, but from Rochester through Zola what's labeled Naturalism leans grim and nihilist. Early critics received Joyce's first books (and Barbellion's Journal) accordingly, sometimes awarding them extra-naturalistic points for having come straight from the whoreson's mouth of a native informant. (Richard Wright's helpfully titled Native Son would be a later example of such critical reception.) And it's true that Joyce and Cummings, like Flaubert and Ibsen, were to varying extents out for revenge.

They were not, however, out for nothingness, and desperate though their circumstances might be, their works were above all else lively: liveliness was their chief defense. Flaubert and Ibsen had violently and despairingly alternated between Romantic/Naturalist inflationary/deflationary antitheses; learning from their examples, Joyce achieved a bizarrely cheering synthesis, and reconstructed the incarnate spirituality of the Church as inspirited carnality.

As for Barbellion, naming his posthumous-to-be collection Enjoying Life exhibited a sense of humor but not sarcasm. He did "enjoy life," and dutifully recording his own disgust, pain, and hopelessness was another method of enjoyment.

Most particularly they were drawn to a certain technique whereby enforced isolation, quotidian (if not downright nauseating) realism, and defiant vibrancy might merge.

Barbellion on Joyce's Portrait: "He gives the flow of the boy's consciousness — rather the trickle of one thing after another.... It is difficult to do. I've tried it in this Journal and failed."

Deliberate production of personality-tinted-or-tainted discourse is at least as old as classical rhetoric. "Stream of consciousness" is only its most recent technique, and in a way the most limited.

As Barbellion noticed, it's also misnamed. What it transcribes isn't a stream, or consciousness, and definitely not silently meditative abstraction staring into an abyss of unframed dust-free mirror, but an inner monologue. Whereas William James wanted to emphasize continuity, linear speech is forced to present one damned blessed word after another. Memories can't be conveyed without a hint of obsession; nonverbal perceptions can't be conveyed without a hint of focus.

Most crucially, an inner monologue takes place in solitude, when the only thing hopping is our antsy brain. Like poetry, it makes nothing happen. Engaging in dialogue with company or trying to learn a novel practice or becoming absorbed in almost anything other than our unlovely self forces (and allows) us to drop the burden of our inner chatter. Which doesn't mean our book has to stop: although the only time you talk to yourself is when you're not talking to anyone else, the only time you reveal yourself is always. If the "stream" is interrupted, we can simply flip to free indirect discourse (personality-tinctured third-person-limited) or drama (a report of direct speech) or narrative with a heavy tincture of narrator (that tried-and-true device common to Swift's satires, nineteenth-century dialect comedy, and the "Nausicaa" and "Eumaeus" episodes of Ulysses).

Given those limitations, a journal or diary is a natural home for inner monologue. Similarly, Joyce's "stream of consciousness" is tailored to the occasion of Ulysses, a day of excruciatingly extended emotional isolation for both male leads, and suits Molly only once she's trapped by insomnia in the dead of night.

But within those limitations, the inner monologue has a peculiar strength: it makes nothing happen. In the midst of sweet-fuck-all it spills a past, a present, alertness, misunderstandings, hopes, vexations, half-quotes, dumb jokes, old clothes, an embedded life dragging world and culture along in its rat's-nest-tangle. In either fiction or journal, no matter how dismal the life might objectively appear (as if there were anything objective about it), it exhibits a liveliness worth living.

| . . . 2021-06-22 |

Way back when I first saw the Hepburn/Grant version of Philip Barry's Holiday, I thought it made no sense. I don't mean anything as eccentric as "real life sense"; I mean, no movie sense. The godheads of Hepburn and Grant are blindingly, staggeringly apparent at a glance, and it's impossible to believe such divinities would let a squirming handful of gray mortals divert them from divine affairs of fate. Watching them wait the movie out was pleasant in itself but I'd hoped for more.

That may be because I already knew the movie's source material via obsessive childhood reading of Burns Mantle's Best Plays series, a sort of Reader's Digest Condensed Books for Broadway. Its condensed Holiday left an impression on my infant soul: it was maudlin, posturing, and (I was assured) sophisticated, with the character of Ned, a sardonic yet utterly feckless alcoholic, providing an attractive role model.

About twenty years after being unsatisfied by the 1938 Holiday, I learned the play had been filmed before, in 1930. It took about twenty more years to snatch an almost-or-then-some unwatchably poor digitization of a bootleg videotape. Since then, Criterion's distributed a much clearer copy as a DVD supplement, and with few exceptions (Stacia Kissick Jones, "FlickChick"), reviewer reactions have confirmed what I already suspected: my fondness for the relic must be more analytical than synthetic. I like to contemplate the structural issues, rotating them under the light like a particularly fucked-up volcanic rock. I can't help it, and why should I, huh? It's very soothing.

I doubt you'd enjoy watching the movie but here, let me show you this rock.

A lot's been happening before the curtain rises. Girl Julia meets boy Johnny at ski resort. Girl neglects to mention that she's fabulously rich and (as is the way of the fabulously rich) insatiably greedy. Boy neglects to mention his plan to take early — almost immediate — retirement, or at least a ten-year sabbatical, and just knock around. Nevertheless they become engaged. (You can understand why Barry wanted to keep this offstage.)

Once the action's underway, a few more bad decisions establish the play as a triangle: Johnny and two sisters, Julia and Linda. Brother Ned serves as chorus.

Julia is beautiful, healthy, intelligent, wealthy, and perfectly comfortable with life as it is. Linda is beautiful, healthy, intelligent, wealthy, and feels suffocated by her surroundings. Johnny is beautiful, healthy, intelligent, now comfortably well-off, and wants to try something other than money-making for a while. Everyone's got the power to do what they claim they want to do at any time. No one wants to assert it. We get the extended dither of an Astaire-Rogers picture without the songs, dances, or Alberto Beddini.

A storyline this scrawny can only be pulled off with a massive dose of audience identification, leveraging our inner obtuseness — our own restively complacent adaptations to our own jerryrigged mousetraps-for-superior-mice — to fog awareness of the play's unlikelihoods. Mopish prepubescent readers can provide that on their own, but on the stage or screen you need star power, and, more expensive yet, three-way star power, since the motivation offered for delay is each party's purported concern for the other two parties, particularly Linda's and Johnny's concern for Julia. Without a Julia, Barry's plot should rightly collapse into a brief meet-cute-and-get-the-hell-out prelude, after which we'd go on to the real movie. (God bless you, Preston Sturges.)

The 1938 film minimizes Julia almost to vanishing point with poor Doris Nolan, three undistinguished credits to her name, barely struggling onto the emulsion. (I suspect the filmmakers wanted to stifle any competition with the controversial charms of Katherine Hepburn.)

But the 1930 film — does it have a sister act! (The poster rightly placed them top of the cast.) Young Mary Astor is a dream Julia: sexy, smarter than her dialogue, and fearlessly direct. You'd have to be crazy to pass her up before devoting a long stretch of dither to the question.

In contrast, as more recent reviewers have complained, Ann Harding's Linda is affected, neurotic, frumpish, and frequently infantile — which is what drives the story. We can understand why this Linda clings to home like a malcontent limpet and we can believe the couple would accept this prospective sister-in-law as a supportive but pitiable ally, and certainly no threat. It would take time to become attached to her and even more to become dependent on her.

What 1930 lacks is a male lead. Robert Ames looks like he'd rather be playing Ned; he displays all the flop-sweat joie de vivre of a Willy Loman. I can believe him and Harding stumbling off to a miserable cohabitation but it would take more than a pair of skis to make him worth Astor's notice.

Admittedly, the role of Johnny, like the role of Julia, doesn't give an actor much to start from. The generic name suits him: he's a Promising Young Man and that's about it. He has no family; well, such things happen. More ominously, this purportedly charming and energetic figure appears to have (almost) no friends of his own, and there's no hint that he's recently immigrated from Poland or Oklahoma. We're told he's good at business, but since the action's confined to domestic sets, we never see him work. He's fully formed before the first-act curtain and aside from one brief vacillation to provide a bit of third-act suspense he never changes a whit.

Cary Grant inspires the necessary confidence and then some, maybe too much; ideally our Johnny should seem capable of making and ruing mistakes — maybe Joel McCrea or James Stewart or Henry Fonda...? What resolved the Johnny problem in 1938 wasn't casting but Donald Ogden Stewart's rewrite of a smaller part he'd himself played on Broadway ten years before.

As already noted, Johnny skimps on personal references. In all three Holidays, all he offers is one couple, named Nick and Susan Potter, and in both movie adaptations Edward Everett Horton plays Nick. Accordingly, reviews and reference works claim he plays the same character. Yeah, and George Miller directed Cybermutt.

Like the play's Potters, 1930's Potters (with gruesome Hedda Hopper as the missus) are natives of the same inconceivably wealthy class as the siblings, distinguished within that class solely by their immaculate frivolity. They don't think about money and they don't strive for more money, but they don't bother to think about or strive for anything else, either. We can appreciate the absence of hypocrisy without enjoying their inane company and without feeling reassured by their sponsorship of Johnny.

Stewart doctored these gaps with ingenious economy: Nick Potter's name is prefixed by "Professor"; Susan is assigned to Jean Dixon, who dedicated her brief cinematic career to taking-no-bullshit; their costumes are downgraded from proper evening wear to academics'-night-out; they boast thoroughly conceivable incomes; they smirk less. That's enough for us to accept them as witnesses to Johnny's laborious ascent, as pledge that his sabbatical won't be devoted to casinos and racetracks, and as evidence that Linda has occasionally ventured outside her mansion and noticed someone outside her family.

And best of all it's still Edward Everett Horton.

| . . . 2021-09-23 |

One of our painter’s greatest concerns during his last years was the judgment of posterity and the uncertain durability of his works. One moment his ever-sensitive imagination would take fire at the idea of an immortal glory, and then he would speak with bitterness of the fragility of canvases and colours. At other times he would enviously cite the old masters who almost all of them had the good fortune to be translated by skilful engravers whose needle or burin had learnt to adapt itself to the nature of their talent, and he keenly regretted that he had not found his own translator. This friability of the painted work, as compared with the stability of the printed work, was one of his habitual themes of conversation.

Or, to paraphrase:

Unmistakably, reproduction as offered by picture magazines and newsreels differs from the [“original,” when anything recognizable as an “original” exists] image seen by the unarmed eye. Uniqueness and transitoriness are as closely linked in the latter as are reproducibility and permanence in the former.

| . . . 2021-09-26 |

Prosody first: infantile babbling and demands; the three-year-old's truncated Mad-Libs-ish narrative efforts ("One time a man mmm mmmm mmm mm-MM-mmh, but mm MMM mmm and THEN mm-mm-MM mmh mmm and THEN....").

Prosody last: my mother, swept halfway into Alzheimerzee, clinging to a few small conversational frames (weather report, mutual backchat, fury) loosely nailed by catchphrases ("Know anything?", "Now you get your rear in gear, buster") and lightly sketched in with nonsense syllables and untranscribable murmur.

I sample that future in late-afternoon cognitive slumps, most vividly while reading, when with no felt transition words and meanings dissolve and swirl in curves which are shaped like thinking but can't be coherently described, a phantasmagoria so drab as to be barely discernible, as much aura as hallucination, "... and THEN" I jerk back, a bit embarrassed at wasting the book's time, retaining a few grains of irrelevance and delusion and an aggrieved sense of a puzzle not worked out.

But this noise of pseudothinking must disconcert less by its thoughtlessness than by its disorder, since intellectually engaging music (Schoenberg, Monk, Funkadelic, Television, ...) so soothingly combs its tangles without loss of focus or imposition of wordly matter. Perhaps the mantra chanter wins similar relief?

In conclusion (and here speechifying's formal undertow — "On the OTHER hand, mmm mmmm mmm mm-MM-mmh, and THUS" — tugs me towards mathematics as, in the undertow's telling, the purest distillation of Mad Libs rhetoric, but I suppose I'm not so pure a formalist after all: that merely sounds false).

mmmm mm mmm ergo like this for a few bars

Sorry, folks, but we're right out of time. So 'til next week, remember: keep smiling with Pepsodent.

J. and I note this especially when reading German while tired; the syntax has such a strong shape that it pulls you along even when meaning goes out the window. Pages and pages of "Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben" entered my consciousness as "German word, German word, German word, German sentence."

| . . . 2022-02-05 |

Behind the Scenes: or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House

by Elizabeth Keckley

I woke up thinking about one of the saddest books I ever read.

Not that sadness was Keckley's goal. She allows only an eighth of her narrative for the arbitrary cruelties, frequent assaults, and occasional rape of slavery, and only to exhibit the triumph of innate dignity. Through hard work, intelligence, talent, charm, and uncompromising rectitude, Keckley earned both freedom and a successful career as modiste to what passed for an American élite. In the first years of Reconstruction, she even felt able to re-establish relations with the family who'd last owned her, whom she'd supported for many years, from whom she'd purchased her freedom for a sum equivalent to six years of salary for a judge, and "I trust that they will not object to the publicity that I give them."

It wasn't until that point, on page 259, that I realized this had not been a safely posthumous publication, or protected by distance or by political alliances. As the book dissolved into a stack of neurotically extortionate letters from Mary Todd Lincoln and a tally of ruinous "loans," my foreboding became more solid than the pages beneath, and when I finally turned to secondary-source material, it was like skipping to the end of a horror novel.

Because I knew that that Keckley's Virginian "family," headed by one of the lawyers who kept Dred Scott enslaved, who'd no more have considered her privacy than they would the privacy of a hunting dog, would not be flattered by violation of their own. I knew the Lincoln family would ignore Keckley's appeal to the tender hearts of the American people in favor of outrage at her impudence. I knew any hope for assistance would be sabotaged by her publisher's hope for scandal. What I'd read was neither a historical memoir nor a daring escape, but a quick march into a long plummet.

What I knew were sad things, and the fact of knowing them made me even sadder. I think there might be places whose readers lack that knowledge, who would be shocked by the sequel to Keckley's book. I wish she'd lived in one of them. I wish I did.

14A

by Laura Riding & George Ellidge

Somebody should've warned Laura Riding that fictional self-portraits must always be unflattering.

Some authors do cameos as a bumbler or a villain (Chaucer, Nabokov, Hammett). Some handicap their stand-ins by erasing their own talent, ambition, or luck (Flaubert, Highsmith). If for some reason they feel they must stay closer to Real (as recalled by the author) Life, at least the author's ineffable personal charms can be reduced without much damage to credibility (Joyce, Proust).

But if the writer instead insists on presenting an image as attractive, intelligent, and righteous as they know themselves to be, readers will provide a discount of their own.

And so from the boldly outlined negative space of 14A pops, with Will Elder vividness, the figure of a cluelessly meddlesome, eyewateringly tasteless Ichabodhisattva Crane. It's an unfair caricature, and I wish she'd never drawn it.

| . . . 2022-02-08 |

Twenty years later, Marian Hooper Adams (AKA Mrs. Henry Adams, AKA Clover) has received two more biographies, featured prominently in at least one more group biography, and been cited in American history, American literature, and women's studies. And we still lack direct access to her extant writings.

A voice so vivid and so constrained deserves all the room we can offer it. "If I were twenty years younger"1 and sufficiently credentialed, I'd gladly devote a decade or two to a fuller edition of her own letters, preferably accompanied by contextual letters from her circle. Although I'm not, maybe someone else is?

1. The Letters of Henry Adams, passim.

| . . . 2022-02-18 |

You’ve said in the past he started out as this sort of wish fulfillment figure of contentment. Obviously, 6E is very dark. Was there a turning point for you where the darkness started creeping into the character?

Serengeti: My personal life came into Kenny, unfortunately or fortunately. I couldn’t hold it at bay that long, just doing this guy that was my retreat. Dave came in. As I look back at it, I’m tripped out. It wasn’t really conscious either. When I step back, it’s like “Jeepers. That’s dark.”

When you say Dave became part of the Kenny character, do you think it’s only negative elements? Or have there been more positive parts of you that have crept in?

Serengeti: It started as therapy, and it transformed into therapy in many different forms. This guy came out of a place where I was just trying to solve some issues. Whatever turns that happened, it’s still part of me trying to work through life. I could be in a situation and Kenny’s voice will come into my head. I use Kenny. He’s like “No, Dave. Come on, fella.” So then Dave was like “You want to come into my head and tell me how everything is so simple? Well, let me complicate things for you.” [...]

What did you mean when you said earlier it’s selfish to work things out in public art?

Serengeti: Life problems, man. You look at them and create stuff from them, instead of solving the issues and living a normal life.

Has turning it into art not been a solution itself?

Serengeti: It’s been overwhelming because there’s no end to it. If you were doing it properly, there would be an end of an album cycle. That art shit, man, you gotta nip it in the bud.

- An Interview with Serengeti by Jack Riedy

(He didn't.)

| . . . 2022-03-09 |

(Attention Conservation Notice: A dispiriting restatement of something you already know, posted in hope of dislodging this snake from my throat so I can return to my usual round of mildly novel trivialities.)

In "The New Puritans," Anne Applebaum repeatedly compares America's prevalent form of ostracism to the self-censorship and informal inquisitons of totalitarian governments, and repeatedly goes on to hedge the comparison since neither the USA nor the UK actually are totalitarian governments. We should have it so simple! In theocratic New England, Fascist states, the Stalinist bloc, or Maoist China, there was only one official line to toe at any one time, whereas here and now the grounds for violent threats or loss of job and reputation will shift whenever we move between city and sprawl, coast and interior, or one Facebook mob and another.

What remains stable is an overwhelming need to assert or assign allegiances, with partisans in each shard applying the same no-quarter-given tactics, and everyone subject to labeling, canceling, and relabeling. Meanwhile the factions represented by local police and courts retain exclusive access to routine literal violence, but they're rarely considered part of "cancel culture" or "fueled by social media."

If we want a historical analogy, a closer one would be society on the brink or in the midst of civil war, such as 1920s Germany, 1950s Algeria, 1960s Vietnam — or 1850s America.

If we want a historical story, here's one I tell myself at bedtime: Reaganauts, hoping to re-establish plutocratic sovereignty and replace the nonpartisan civil service with cronies, clients, and profiteers, had intended to brake their DeLorean at 1875 or so.1 But strategic allies tend to become more intrusive over time, and over time the Southern Strategy tugged at the wheel and kicked at the accelerator and now our dear plutocrats have to straddle a chaos of bushwacking and jayhawking true-believers.

I suppose my assigned partisanal shard might draw some small rainbow-with-a-pot-of-justice-at-the-end comfort from the result of 1850s' previous go-round:

"For my own part," he [Lincoln] said, "I consider the central idea pervading this struggle is the necessity that is upon us, of proving that popular government is not an absurdity. We must settle this question now, whether in a free government the minority have the right to break up the government whenever they choose. If we fail it will go far to prove the incapability of the people to govern themselves."– John Hay's White House diary, 7 May 1861

Stirring words, but they were only spoken because territory-hungry slaveholders had panicked in the face of the first popular vote to bring a (non-radical gradualist) abolitionist into the executive branch. As later events showed, they should have just waited the upstart out: the Supreme Court routinely favored slaveholder rights over state rights, the Democrats had kept control of the inherently minority-rule-friendly Senate, and the Republicans had lost ten seats in the House. Instead they took an option which was blatantly non-viable, since a Union and a Confederacy equally committed to expansion would've been forced to maintain a continent-wide fully militarized sequel to Bloody Kansas until one or the other was re-absorbed.

Alternatively, if impatient secessionists had been fortunate or sly enough to posess an in-power president to act as national figurehead, and nation-wide propaganda platforms, and a long-term plan for repressing majority rule, and widespread support amongst military and police and the wealthiest business class, they could've chosen the less complex option of a coup.

1. Their preferred destination, the Gilded Age, had its own, more passive, Southern Strategy: resentful traitors were welcome to their whitewashed histories and Confederate memorials so long as they didn't interfere with finance.

... they are tramping over the city in search of a place for a statue of Thomas Jefferson. Our northern politicians show sense by keeping out of the monument business. They let the southerners put up all the sentimental statues they want. No federalist leader, not even Washington, has a portrait statue here, and no republican, not even Lincoln, done by Congress; but the democrats have all their defeated generals caricatured to immortality....And then as now, propaganda worked: lynchings stopped being news, Jim Crow laws normalized, and finally Woodrow Wilson was even able to resegregate the federal government.– Henry Adams, May 8, 1904

| . . . 2022-03-10 |

John Hay's ideal in this period was to be a gentleman and a man of culture. "His natural propensity for culture," wrote James Ford Rhodes, "was fostered by the reading of books and by mingling in the best society." [...] Hay was more at home with such people, but there was the difficulty that the men he found there were living active lives while he was merely searching for good conversation.- John Hay: From Poetry to Politics by Tyler Dennett

| . . . 2022-03-22 |

On particularly grueling drives, a stream of varied music can delay my focal retreat from the too-much road into the swirling fluff which fills my skull.

It was to meet a similar need, I think, that a hundred or so pages into Appleseed I began to visualize its comics-jam adaptation:

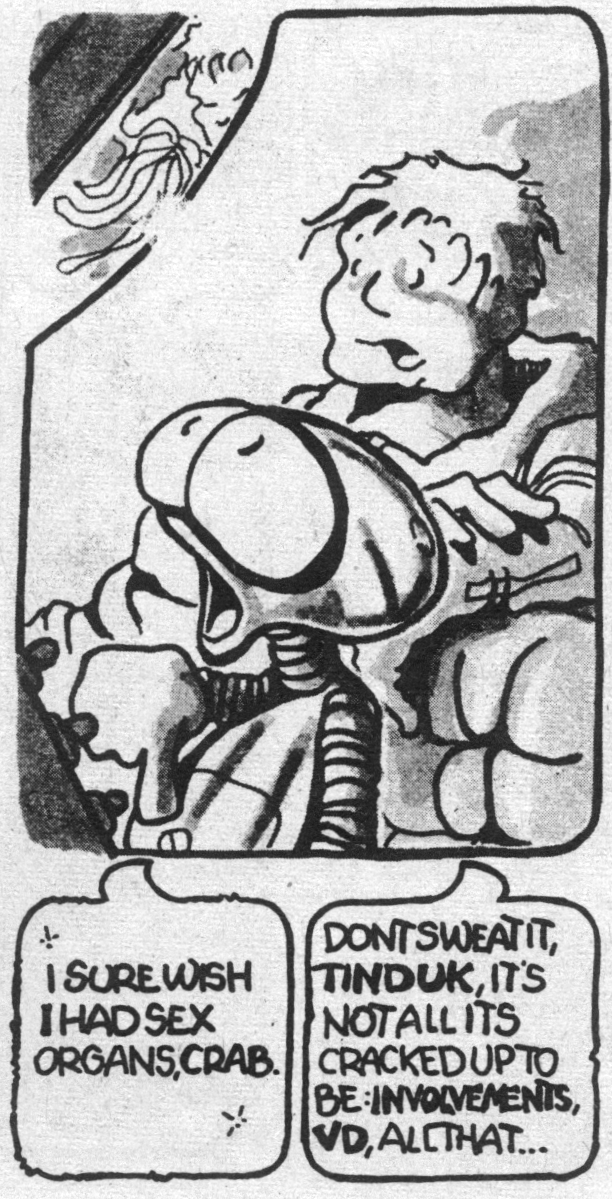

Vaughan Bodé providing the leading man (as pictured at right), the unpredictable inevitable ultraviolence and megaviolence, and the patois of icky-sticky-cutesy-whoops and primeval gangsta; Greg Irons on villains; color palette and cultural references courtesy of Robert Williams; Barney Steel's heterodeformative Armageddon; Victor Moscoso squeezing in a Mr. Penis cameo; and, in the role of Clute's prose, the horror vacui penwork of S. Clay Wilson at its most amphetamineralized, capable of petrifying any action, no matter how excessive or malodorous, into gaslit tableaux.

| . . . before . . . | . . . after . . . |

Copyright to contributed work and quoted correspondence remains with the original authors.

Public domain work remains in the public domain.

All other material: Copyright 2022 Ray Davis.